–From the ten most beautiful experiments by George Johnson

Ivan Pavlov, a famous Russian scientist, became well-known for his experiments with seven dogs. Instead of conducting harsh experiments that involved dissecting live animals, Pavlov, who was a skilled surgeon, preferred a more gradual approach. He used anesthesia to modify organs for fluid collection, reserving intense procedures for better understanding the body’s functions, although he did so reluctantly. He recognized the ethical challenge and felt sorry for disturbing the intricate beauty of a living organism. Yet, he endured this discomfort in his quest to uncover truths for the benefit of humanity.

Ivan Pavlov initially wanted to become a Roman Orthodox priest like his father. However, his interests changed when he secretly read books like “On the Origin of Species” and “Physiology of Common Life” at the village library. Intrigued by the idea of understanding animals scientifically, he decided to stop studying to become a priest and instead pursued education in Saint Petersburg.

Experiments by Ivan Pavlov

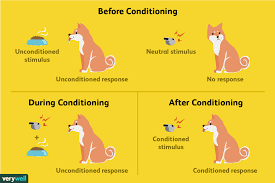

Ivan Pavlov understood that salivation had several benefits, like helping food move smoothly to the stomach and preparing a special juice for digestion. Sensors in the stomach and duodenum, part of the nervous system, analyzed the food and signaled the body to produce the right digestive fluids. To check how much saliva the dogs produced and what it was made of, Ivan Pavlov performed a small operation. While the dogs were asleep from anesthesia, he changed the duct opening from a salivary gland to the outside of the chin or cheek and stitched it in place. After the cut healed, he collected and studied the fluid. Pavlov noticed that animals could start salivating not only when they saw or ate food but also when they saw a bowl or heard a creaky door hinge during mealtime. He called these reactions “Psychic secretions.”

Unlike natural reflexes, these reactions are learned and can change. For example, if a dog sees meat but it’s taken away repeatedly, it starts salivating less over time. This change in the reflex is clear. But when the dog finally gets to taste the meat again, the saliva reaction comes back. Although Pavlov thought about explaining this physically, he found it puzzling why the unpleasant touch of acid could also make saliva come out. This made him realize that since we can’t know exactly what’s going on inside an animal, fully understanding their inner feelings is challenging.

Pavlov suggested that scientists should focus on understanding how animals connect their reactions to things around them. For example, a dog naturally salivates when it smells meat. But if you show the dog something else while giving it meat, it will start salivating at the sight of that thing too. This also works for protective reactions. If a dog tastes harmless acid dyed black with India ink, it will start salivating protectively when it sees black water. Once the dog realizes the acid is not harmful, the reaction goes away, but it can come back if the dog tastes the acid again.

Pavlov’s lab studied how dogs understand time. They trained a dog to start salivating when it saw a flashlight. Then, they purposely waited for three minutes before showing the light. The dog learned to expect the delay, and its mouth would start watering three minutes after seeing the light. This learning method is popularly known as Classical conditioning. Ivan Pavlov believed this careful way of experimenting could help solve the long-standing problem of understanding time that philosophers have wondered about for years. He stressed the importance of keeping the experiments consistent, like using the same surroundings, to avoid changes in the dog’s reactions. If a dog learned something in one place, doing the same experiment in a different place might not work. Ivan Pavlov also pointed out that any unexpected things around the dog, like other stimuli or disturbances, could affect the experiment’s accuracy.

Ivan Pavlov and his team showed that a dog can have basic musical skills. They trained a dog to start salivating when it heard a specific set of musical notes. They associated four going-up notes with a bit of food but didn’t reward the same notes played in a going-down order. The dog learned to tell the difference between the two sequences. Also, when the dog heard twenty-two different combinations of the same note, it reacted based on whether the pitch was going up or down. Ivan Pavlov thought this skill was like his role as a scientist conducting experiments.

In 1935, as a tribute, Pavlov’s students gave him a photo album with pictures of forty of his dogs. Later, they built a decorative fountain called “Monumentum to a Dog” at the institute, featuring a big dog at the center with reliefs showing lab scenes and quotes from Pavlov.

Ivan Pavlov’s Legacy

Today, Ivan Pavlov’s discovery on classical conditioning have become an integral part of the psychiatric treatment. Techniques like aversion therapy and systematic desensitization are derived from the Pavlovian theory. Additionally animal training using operant conditioning applies Pavlovian conditioning principles by reinforcing desired behaviours through positive consequences and getting rid of unwanted behaviours through negative consequences.

“The naturalist must consider only one thing: what is the relation of this or that external reaction of the animal to the phenomena of the external world?” This quote from Ivan Pavlov called for naturalists to prioritize the relationship between external reactions and the external world. This approach has fostered scientific rigor, objective measurement, and a focus on observable behaviours.